History of TheBaltimore Eagle

And Its Symbol

The Eagle

1970. New York City. The streets are still smoldering from the Stonewall Riots, “gay rights” has become a movement, and an old longshoreman’s tavern named Eagle Open Kitchen has just closed its doors. This is where the first Eagle bar was born.

It was renamed “The Eagle’s Nest”. Inside, the walls were painted black, biker groups and sports clubs began holding meetings, and soon the place became a popular spot for traditionally masculine-presenting gay men. Amid the tension of homophobia in their everyday life, these men found a place of respite at The Eagle’s Nest. It was a “safe space” before that term became part of our vernacular. When patrons of The Eagle’s Nest left New York City, they carried with them that sense of community; and The Eagle’s Nest served as inspiration for new Eagle bars that began opening doors in cities like San Francisco, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and even as far away as London.

The Baltimore Eagle pays homage to the history of the leather and kink communities. In the spirit and tradition of fellowship, we promise to provide you with a safe, judgment-free space to congregate and celebrate your true self. We hope you come again soon, and that you always leave satisfied.

The Toms

Tom of Finland

In order to understand the story of The Baltimore Eagle and the symbol that represents it, we need to begin by understanding their inspiration. That inspiration is largely bound up in the histories of two men, both named Tom.

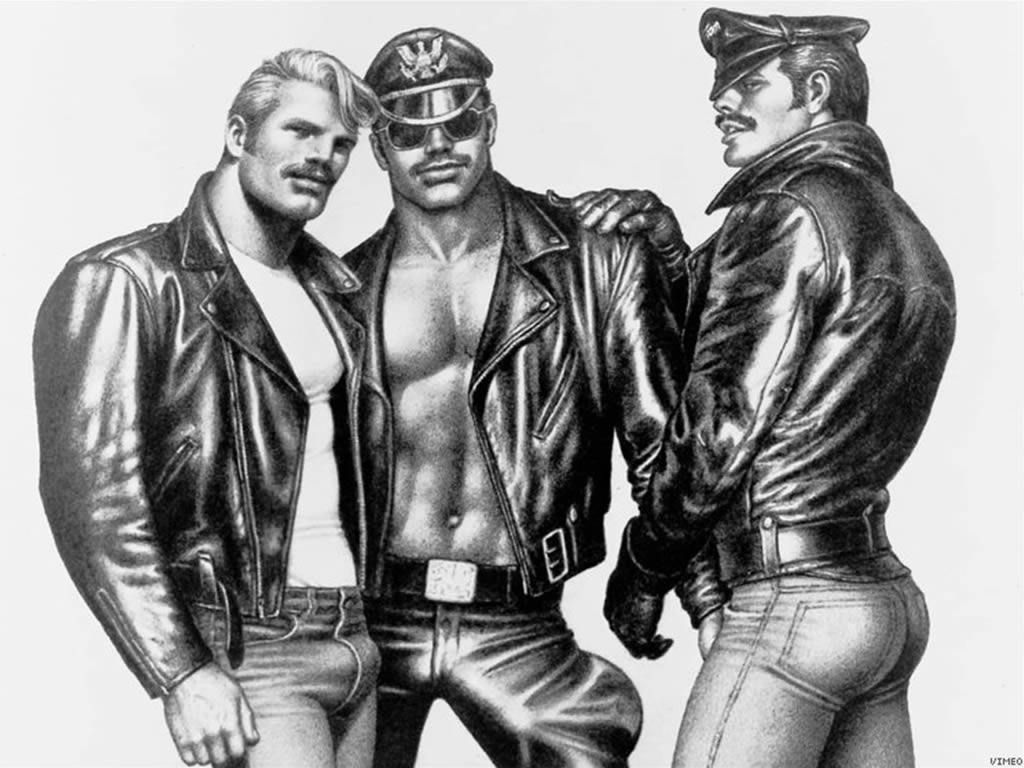

Our first ‘Tom’ didn’t begin his life with that name; it was chosen for him because it was easy for his English-speaking friends to pronounce. Over the last half-century or more, Touko Laaksonen, known most commonly as Tom of Finland, has had a profound influence on LGBT iconography as a whole and has been universally recognized as the foundational figure behind many of the symbols commonly associated with leather culture throughout the world.

Tom of Finland began drawing images of well-muscled men while a student in Helsinki in the late 1930’s. Sadly, few of Tom’s earliest works survive. In a Europe that was becoming increasingly puritanical and regimented with the rise of National Socialism and Soviet Communism, Tom (perhaps rightly) thought that his images might place him or his family under scrutiny, so he destroyed nearly all of them.

During his service in the Finnish army during World War II, Tom became fascinated with military symbols, uniforms, and badges of rank. When Tom went back to his art after the war, he was attracted by the juxtaposition of rebellion and regulation, and he started combining hyper-masculine male depictions (similar to those being drawn at the time by American artist George Quaintance) with symbols of authority, discipline, and strength. Though many of his works were plainly homoerotic, they flew in the face of stereotypical views that saw gay men as weak or effeminate. Tom’s men were lumberjacks, and policemen, and sailors, and soldiers; Tom’s men were men who clearly liked being men.

In the 1960s, greater sexual freedoms in general led to the decriminalization of male sexual images in U.S. publications, and Tom’s drawings reached a much wider circulation than they had in the years immediately following WWII. Though he became particularly popular in America, the early 1970s saw his work being reproduced all over the world. In the decades since then, Tom’s distinctive artistic style has been copied so many times by so many people that it has become almost impossible for anyone but an expert to tell many of his drawings from those that he inspired.

Tom’s men were men who clearly liked being men

When our second ‘Tom’, Tom Kiple, decided to open a club in Baltimore in 1991, there were already a few leather-friendly bars in the city (most notably The Porthole and The Gallery), but none had yet established themselves as a ‘home away from home’ for the leather community. Kiple wanted to change that by presenting his club as first-and-foremost a leather bar. He wanted a name that would make that point clear to his prospective clientele by connecting it to an icon that already had meaning to them: an eagle.

During the 60s and 70s, the rise of openly gay communities in the larger cities of the U.S. met with resistance that often turned violent, and LGBT bars and clubs became safe havens where society’s inequities – and those who perpetuated them – were unwelcome. These bars and clubs also became meeting places for an increasingly activist community that sought recognition without prejudice. One such club, prominent in New York, was The Eagle’s Nest, a Leather/Levi bar founded in 1970.

Contrary to the misperception engendered by their ‘fringe’ status, the patrons and owners of The Eagle’s Nest were huge proponents of community outreach, and the efforts they coordinated on behalf of charitable organizations went a long way toward easing local tensions. Over the next few years, the term ‘Eagle’ became synonymous with ‘sanctuary’, a judgment-free place where members of the leather community could gather and be themselves. Eagle Bars began opening all over the world, not as part of a brand, but as a movement.

According to one story, the original hand-drawn logo for The Baltimore Eagle was modeled after the hood ornament of a 1957 Ford Thunderbird. When ownership of the club and its brand were transferred in 2012, the new proprietors recognized that the old bird needed a little facelift. In the new design, the original wing configuration has been given a slight curve and talons have been added. The ‘Baltimore Eagle’ name has been placed on a round medallion, and the whole device has been given a metal sheen similar to police and military badges. The updated logo pays homage to both Tom Kiple’s original design and the influence that Tom of Finland has had on the leather community worldwide and because the Eagle symbol descends from military insignia the Eagle’s head always faces its right wing.

According to one story, the original hand-drawn logo for The Baltimore Eagle was modeled after the hood ornament of a 1957 Ford Thunderbird. When ownership of the club and its brand were transferred in 2012, the new proprietors recognized that the old bird needed a little facelift. In the new design, the original wing configuration has been given a slight curve and talons have been added. The ‘Baltimore Eagle’ name has been placed on a round medallion, and the whole device has been given a metal sheen similar to police and military badges. The updated logo pays homage to both Tom Kiple’s original design and the influence that Tom of Finland has had on the leather community worldwide and because the Eagle symbol descends from military insignia the Eagle’s head always faces its right wing.

Rich Richardson

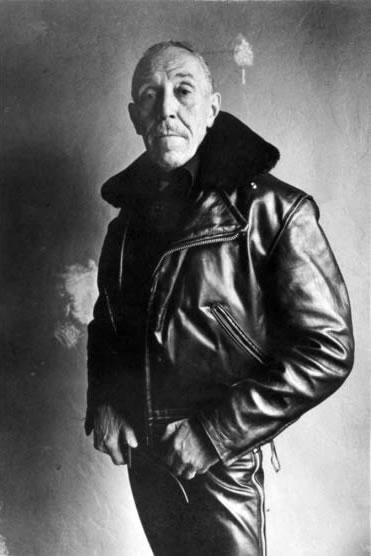

Richard B. Richardson, who took over management of the Baltimore Eagle in 1994 after Tom Kiple moved on to other ventures, wasn’t involved in the founding of the Baltimore Eagle or the creation of its symbol, but he was instrumental in defining its purpose and expanding its reputation.

Richard moved to Baltimore from Atlanta to pursue his dream of owning an Eagle club, and he was deeply involved in every aspect of bar operations until his death in 2007. Richard was always fascinated with the outlaw mystique and the freedom it represented. One of his favorite phrases was: ‘Leathermen do whatever the hell they want,’ an expression which was used often during his tenure to describe the style of the club he ran.

Richard was keenly aware of the leather community’s history, and it was largely through his efforts that the Baltimore Eagle became a home for charitable events, gatherings, and contests both local and national. The Baltimore Eagle would certainly not be either so fondly remembered or so widely recognized if not for Richard, and the club’s future owes a debt of thanks to the past he left it.

Also worthy of special mention are Richard’s long-time friends and neighbors, real estate developers Charles and Ian Parrish. Charles’s connection with the Eagle began in 1962 when the tavern was among his first stops upon returning from years of military service abroad (it was then named Al Wynn’s). In fact, it was Charles who originally acquired and sold the building to Eagle Founder, Tom Kiple. Charles was proud to have been the Eagle’s first customer.

After Richard’s death and with no heirs to speak of, the future of the Baltimore Eagle was tenuous. Further complications arising out of the intolerance of a few community members nearly extinguished the Eagle. However, inspired by an outpouring of support from patrons of the Eagle, the Parrishes stepped in and led a massive reconstruction and revitalization of what Ian Parrish called “a Baltimore landmark, and a special, judgment-free place worth saving.” The spirit of this landmark tavern was restored with such love and goodwill that even the opposition joined in support at the Grand Reopening; and the Eagle heralded yet another generation of fellowship at our home away from home.

This narrative was compiled with input from several expert sources, including: Jakob VanLammeren and his group at the Leather Archives and Museum in Chicago, IL; ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the University of Southern California; the staff and patrons of Eagle NYC; and finally, the staff and patrons of the Baltimore Eagle, without whom there would have been no history to write.